Imagine this scenario: a colleague offers to flip a coin and give you $20 if it lands on heads. If it lands on tails, you give him $20. Stop and ponder; would you accept that bet? For most of us, the answer is no. Behavioral science experts Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman performed an experiment which resulted in a clear example of human bias towards losses. The experiment involved asking people if they would accept a bet based on the flip of a coin. If the coin came up tails the person would lose $100, and if it came up heads they would win $200. The results of the experiment showed that on average people needed to gain about twice as much as they were willing to lose in order to proceed forward with the bet. This tendency reflects loss aversion, or the idea that losses generally have a much larger psychological impact than gains of the same size.

You likely experience this phenomenon daily. Ever purchased something knowing you’d likely return it, but the longer you keep it the more attached you get? Sending the item back now feels like a loss. The longer we’ve waited to be seated at a restaurant, the harder it becomes to leave, as it feels as if the time we’ve invested would then be lost. The more we try to fit a new couch through a too-narrow entryway, the less inclined we are to give up and accept that we need a smaller couch, and the more steadfast we become in making it fit. It seems that sometimes we will persist with a belief or course-of-action long after it is rational to do so: we feel trapped by what we have already committed.

Although a fascinating piece of knowledge about human behavior, what does the concept of loss aversion have to do with the workplace?

As leaders, knowing that losses have a tremendous psychological impact can cloud judgement when it comes to truly evaluating employee performance. We have a tendency to double down with those we’ve invested time with yet who continue to underperform.

“B” and “C” Players

A less enjoyable component of management is the act of working with and

coaching the perpetual underperformers. Every department has them, every leader

has struggled with them, and some may even have a few who come to mind

immediately. They are the few who we try to encourage, who we try to train, and

for whom we hold out hope that change will come, but it can seem like an

endless cycle of performance management and frustration.

We all recognize “A” Players. Within most organizations, there is even room for the competent, steady “B” performers who balance their work and personal lives while still performing a significant amount of tasks that need to be done. They stay in their lane, don’t require a great deal of attention, and they get the job done.

On the other end of the spectrum, “C” Players sometimes make up the smallest segment of the team yet require the most time and attention. They are the employees with a constant litany of excuses – a vehicle is broken, someone is sick, excessive days are missed, and the workload either gets passed to someone else or delayed altogether. They walk the fine line between “good enough to get by” and “fireable offense worthy of termination.” They are granted continual employment primarily because the act of hiring, training and managing someone you don’t know is sometimes more intimidating than continuing to deal with the perpetual issues of the presently employed “C” performer.

Stop Doubling Down

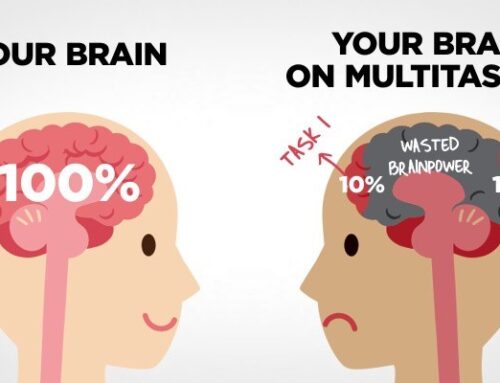

It’s time to step away from the fear of losing $100 and focus instead on the

opportunity cost of not winning $200. The obvious unintended consequence

of having a seat filled with an underperformer is having it not filled

by a significant contributor. What rarely is considered is the impact on those

who are current significant contributors; there is little more frustrating than

having your own success consistently hampered by another person’s incompetence.

If the majority of your team is working hard, producing great results with

tremendous collaboration, what message are you sending by supporting the 10

percent who are doing the opposite? How long do “varsity players” want to be

surrounded by sub-par athletes?

Beyond performance issues, it is likely time to topgrade when:

- The individual is the central cause or perpetual perpetrator of office drama

- Co-workers (or possibly worse, clients) have taken note of the incompetence

- The employee has an apathetic attitude

- He or she ignores actionable feedback

- The individual handles emotions poorly, mistaking the work environment as a therapist’s office

- You spend more than ten minutes a week, week after week, dealing with issues created by the employee

Toxic Workers, a Harvard Business School study of more than 60,000 employees found that “a superstar performer–one that models desired values and delivers consistent performance” brings in more than $5,300 in cost savings to a company. Avoiding a toxic hire, or letting one go quickly, delivers $12,500 in cost savings.

Sometimes, it truly is best to return the item, leave the overcrowded restaurant, or succumb to a smaller couch. Instead of experiencing a loss, you might actually gain the improved morale of the entire workforce. Instead of experiencing a feeling of loss over time invested, you might actually gain more time to invest in those worth investing in. Instead of feeling the loss of an employee, you might actually gain a key contributor you would not have otherwise hired.

—Karen Schmidt